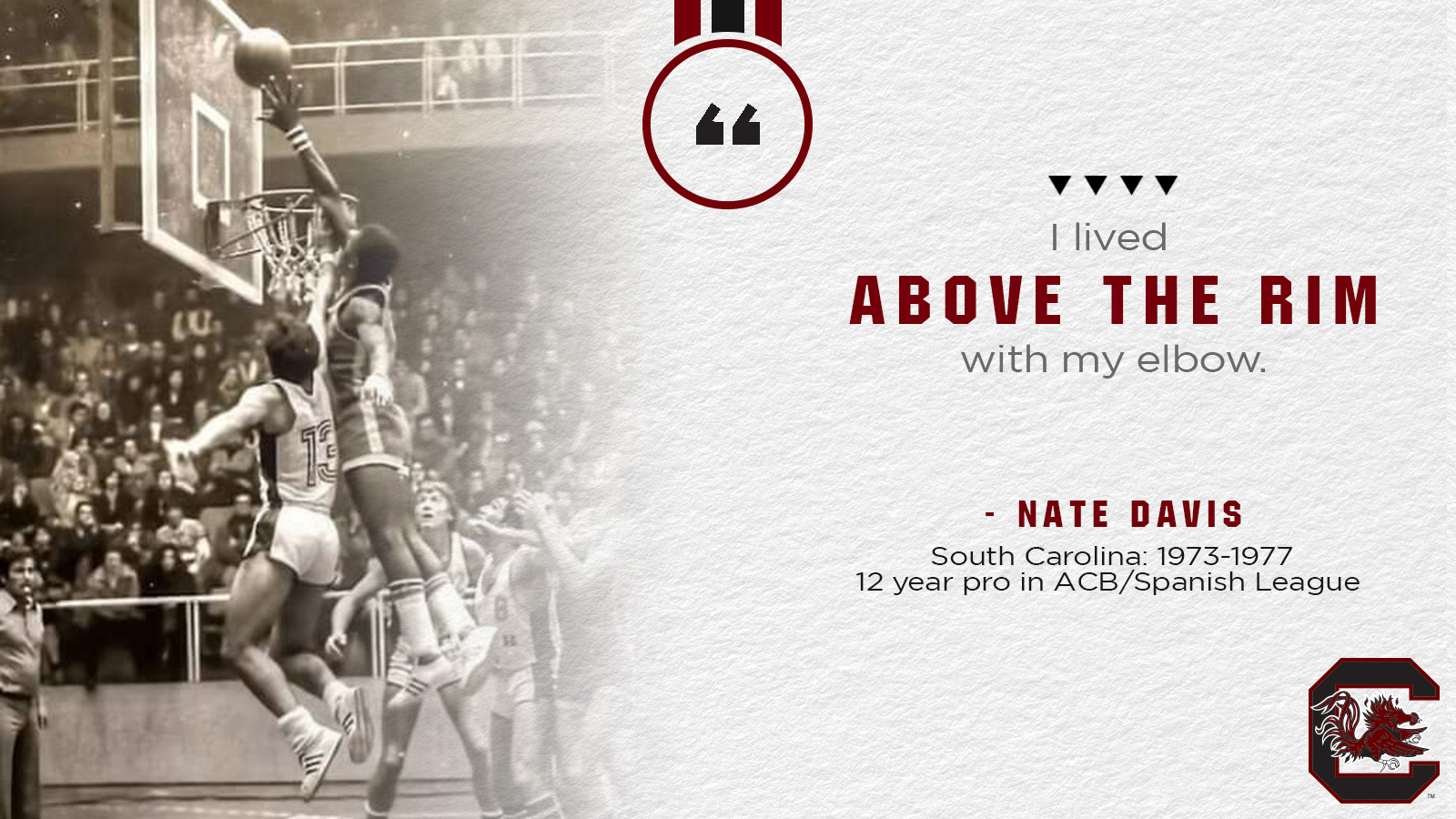

Catching Up with Basketball Legend Nate Davis

Nate Davis played with some of the all-time greats at South Carolina, and the high-flying slam dunker and shot blocker may be one of the more under-appreciated stars in Gamecock basketball history.

“I was a great leaper. I lived above the rim with my elbow,” Davis said.

“When I went to Carolina, I was honored. When I met Coach (Frank) McGuire, it was like meeting the king of basketball! As long as I live, I would never regret going to Carolina.”

Davis (1973-77) played at South Carolina at a time when college basketball wasn’t on every channel and before ESPN hit the air waves, which meant there were no SportsCenter highlights. Having left the ACC a couple of years before he arrived on campus, Davis and Coach Frank McGuire’s Gamecocks played as an independent, but that didn’t stop him from putting on a show. Oddly enough, his college career almost didn’t happen.

The Columbia native starred at Eau Claire high school and was considering joining the military before finding out there was an opportunity to continue his education and play basketball in his own back yard.

“My senior year was one of the greatest years for me with basketball,” Davis said. “I didn’t even know Carolina was recruiting me. I had no idea! (Former Gamecock) Bobby Cremins was an assistant coach at the time for Coach (McGuire). I had no idea that any school was interested in me at all. I was up at Fort Jackson during my senior year to take an exam to go into the United States Marine Corps. My assistant coach came up there and took me from Fort Jackson to tell me that I’m going to Carolina and that I had a scholarship.

“One day, I was tying my tennis shoes, and Bobby (Cremins) just appeared. It was like something out of Star Trek! I didn’t know he was in the gym. He said, ‘We are interested in you coming to Carolina.’ I could have fainted! I had no idea. I told him that I would love to! It was a perfect setup. I just told him he had to talk to my dad. So, my dad signed the scholarship and the rest was history.”

Davis had the good fortune of playing alongside South Carolina legend Alex English early in his career, and he led the Gamecocks in scoring as a senior with 15.7 points per game. The State newspaper ranked him among South Carolina’s top 25 (16th) men’s basketball players of all time back in 2016. He scored 1,345 points in his career and helped the Gamecocks reach the NCAA Tournament in his freshman season as South Carolina posted a 22-5 record. Davis was grateful for his opportunity.

“It changed my life,” Davis said. “I was a young teenage boy, and when I left, I was a man. Not only because of basketball. He taught you how to be a man, and how to be on time. He gave you character.

“I worked my butt off. Brian Winters was my roommate as a freshman. He taught me how to really shoot the basketball. I was a good player in high school, but I needed to take my game to the next level.”

“We were a brotherhood. I walked through campus and never felt hate.”

EARLY INFLUENCES

Before McGuire and Winter’s tutelage, Davis spent a lot of time as a youngster working on his grandfather’s farm. He didn’t know much about basketball until his cousin, Harrison Davis, taught him the game.

“He was a superstar basketball player in Winston-Salem, North Carolina,” Davis said. “I begged my dad to go up and hang out with him. I was just a farm boy, and he taught me how to play basketball. I was in great shape from running behind chickens and goats.

“When I was jumping, it came easy. So dunking was nothing. I was a late bloomer in basketball. I stayed with him for two summers, and the rest is history. I got so good, when I went to junior high school, they wouldn’t let me play because I was too good to play.”

Davis was permitted to play on Eau Claire High School’s JV team and then played two games before being brought up to start on the varsity team.

Growing up during the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, Davis experienced his share of racism. As he grew older and came to South Carolina, which began offering scholarships to black student-athletes in 1969, he was grateful for pioneers who had come before him for paving the way.

“From the day first day I set foot on Carolina and until the day I graduated, I didn’t ever experience racism (at the University),” Davis said. “We were heroes, man! I never heard the n-word on my basketball team. Most of those guys were from New York. We had Jewish players and Irish and Italian players. We were a brotherhood. I walked through campus and never felt hate. I never felt any type of racism.

“Now, I grew up with it where I couldn’t go into restaurants or drink from a water fountain. I couldn’t go to white schools until the Civil Rights movement. A lot of my friends at Eau Claire were white and at Carolina. Coach McGuire made that atmosphere like that. Casey Manning was the first African-American basketball player here. Alex (English) was the first Columbia African-American ball player here. I was the third.”

As for his time on the court, Davis relishes his experiences in the Garnet and Black.

“Every game for me at Carolina was like an all-star game,” Davis said. “Every time I got on that court; it was a tremendous honor to be an African-American on that court. It was an honor to play with the great Alex English! That was one of the reasons I wanted to play there. Alex took me under his wing, and Brian took me under his wing. Everybody was great. We had good times, and we won games. I will never regret going to Carolina.”

PROFESSIONAL LIFE

After graduating in 1977, Davis was drafted in the fifth round of the NBA draft by the Chicago Bulls. After working out with the team that summer, Davis was released, but he found a home playing professionally in Spain where he starred for a dozen years.

“In Spain I averaged between 34 and 40 points per game,” Davis said. “I was the leading scorer four years in a row. I’ve been called the Michael Jordan of Spain.”

Ironically, it was Davis’ high-flying ability that contributed in hurting his career.

“I had 12 seasons in Spain,” Davis said. “Eight official years, and the other years, I was hurt. In my twelfth year, I got hurt in a game. I was guarding this guy who was 6’9″, and he did a head fake. I don’t know why I went for it, and I was so high in the air, his shoulder hit my ankles and I flipped over. All my weight came down on my right shoulder and broke all that up. I was in the hospital for seven days. They had to put my arm back together.”

Unfortunately, that was only the beginning of a difficult year for Davis. His wife, Annie-Lou Davis, died in 1988 from complications with AIDS, which she acquired after a blood transfusion.

“My son, Matthew, was premature at six months and when she was pregnant with him, she started hemorrhaging and lost five units of blood,” Davis recalled. “They gave her five units back as a blood transfusion, and we found out later that one of the units was infected with the HIV virus. It’s didn’t take effect on her until about three years later. We didn’t know until later, and by then there was nothing we could do.

“It was devastating. She was only 29 years old.”

Prior to her death, Davis brought his wife to Georgia for hospice care. He needed to find work, and it was his University family that helped him out. He contacted Coach McGuire, and he suggested he go see Cremins, who was now the head coach at Georgia Tech, to find a job.

“I was his first recruit. I needed a job,” Davis said. “I went down to Bobby’s office. It was a like a family reunion. I told him my wife was sick with AIDS. I told him I had just moved to Atlanta and I needed a job to take care of my family. Bobby got on the phone and called the region manager of Federal Express. The guy hired me over the phone. I’ll never forget it. A lot of people don’t know about the help I got from Bobby Cremins and Coach McGuire.

“They helped me get a scholarship and then a degree and they treated me like a human being. I’m very grateful.”

“Carolina has a big, special place in my heart.”

BACK HOME

Davis worked for Federal Express for 15 years before retiring and resettling in Columbia three years ago. Since then, he has been a regular at South Carolina men’s and women’s basketball games and has reconnected with English, Manning, and many others in the South Carolina Athletics community.

Having enjoyed good experiences with his alma mater, Davis is saddened when he sees instances of racism and social injustice today.

“I never thought I’d see what I experienced as a kid, happening now,” Davis said. “We must come together as one. We are the same people. We are America! We live in the same neighborhood. We live in the same state. I didn’t ask to be black. God did it for His glory. He gave me what He thought was right for me.

“God, who created us, loves variety. Look at all the trees. Look at all the birds. Every color is beautiful. My dad had blond hair and blue eyes. My mother was Cherokee Indian. She was dark with long black hair. My great, great, great grandfather in Jenkinsville, had the Davis Plantation. Think about that; the master of the plantation was white. I have blue eyes myself, and I’m a dark-skinned African American. Our hearts need to be changed. Racism comes from a disease called sin. The only way to get rid of this disease is to have God in our lives. We have to change inside our hearts We’re not born racists; it’s taught.”

After being honored in Spain’s basketball Hall of Fame, the 66-year-old Davis hopes to be nominated for the University of South Carolina Association of Lettermen’s Athletics Hall of Fame in the near future.

“Carolina has a big, special place in my heart,” Davis said. “When I stepped on that campus, they treated me with dignity and pride. They treated me like I was a human being.”

Follow Nate Davis on Instagram: @natedavisjump