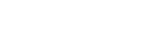

Harold White Stands as a Pioneer for Gamecock Football/Athletics

Feb. 10, 2016

Most of Harold White’s nearly four decades in the South Carolina Athletics Department were spent as an academic advisor or administrator, but nearly everyone who knows him, still addresses the man as “Coach.” Retired since 2007, White became South Carolina’s first African-American coach when he was hired by former head football coach Paul Dietzel as a graduate assistant in 1971 at the age of 31.

“Everyone calls me ‘Coach,’ ” White said. “Even today, I get more joy from everybody I had the chance to know, whether it’s black or white; male or female. I feel good about my career. I was a full time coach when I got there, but I came in as a graduate assistant. I had a wife and two kids at the time. In 1971, there were six black football players who came in with me. There were a couple basketball players that came in that year too. I coached on the freshman football team in 1971 and 1972.”

He took off his whistle and became an academic counselor in 1973, taking charge of academic support for Gamecock student-athletes, and later holding the title of Senior Associate Athletics Director for Academic Support and Student Services. Had White stayed in coaching, he probably would have been just as successful, but he still made an impact every step of the way.

Changing Times

After graduating from South Carolina State University, White began a career in high school teaching and coaching in the Palmetto State, which eventually landed him at Lakeview High School in West Columbia. It was around this time in the mid-1960s when traditionally “white colleges” around the country began to recruit black student-athletes.

White had contacted South Carolina’s staff about a running back named Arnold Carter, whom he thought would be a good fit for the Gamecocks, but ultimately ended up at Purdue University. Two years later, White began working for a summer program known as Upward Bound, and that led to a meeting with Coach Dietzel, who realized there was a need to have better a connection with the African-American community.

“Coach Dietzel took me to lunch,” White said. “He felt like South Carolina needed a black coach. You had Freddie Solomon coming out of Sumter High School around that time, along with several other high profile black athletes who were coming out of some of the (South Carolina) high schools. A lot of the black guys around then went to schools in the Big 10. Solomon ended up at Tampa and then played with the 49ers in the NFL, but there were going to be more black athletes at South Carolina now. Coach Dietzel offered me a position in 1971, and I took it. I think there were six black athletes that came to South Carolina (football) that year. The next year it really took off.”

Casey Manning, who was South Carolina’s first African-American basketball student-athlete and had already been with the Gamecocks for two years in 1971, understood the significance of White’s hiring.

“It was huge,” Manning said. “He’s a true pioneer in that sense. The best decision Paul Dietzel ever made was to hire Harold White. He was a local guy, who knew all of the local politics. He knew everybody, and in addition to that, he was, and is, a terrific human being. He’s a very caring man who always saw both sides of an issue. He was always fair.”

Through the years, I’d like to think I had some role in helping them become very productive citizens. I just like to hear that they are doing well.

Harold White

While there were racial tensions across the country as schools and athletics programs integrated around this time, White acknowledged that the transition at South Carolina was relatively smooth.

“We didn’t have those kind of problems with the black and white players,” White said. “Many of them became the best of friends, and a lot of them are still friends today. We didn’t have the flare ups that happened on a lot of other campuses. That’s not to say everything went OK every day, but from what we heard about what happened at other schools, we were OK. I think I had a little bit of a role in that. I think we did well.”

White recalled a situation that had potential for some conflict when Dietzel implemented a prohibition on mustaches and long hair, which were both popular in the day.

“It was tough,” White said. “For the black players, they all had mustaches. That’s just what we did. So now, I had to shave my mustache. The word got around to a lot of friends I went to college with, and they kept saying ‘tell me that man didn’t make you cut your mustache.’ I did.”

The issue was somewhat diffused a short time later when White gathered the African-American student-athletes on the team to let them know that Dietzel was offering a compromise.

“Coach Dietzel was going to have a meeting after practice, and he was going to announce that he was backing off that rule a little bit, and that you could have a mustache, but it could only come down so far,” White said. “I told them that all I wanted them to hear was that you can have a mustache. He’s going to tell it his way. So just listen and accept it. We got the mustaches, so we were pleased, but the boys who wanted the long hair down their backs, they were more upset.”

Tackling His Biggest Role

A couple of years later, limits were placed on the number of fulltime coaches college football programs could have on their staff, and with the elimination of freshman teams as first-year college student-athletes were now allowed to play on the varsity team, White found a new home with the Gamecocks.

“I was interested in the academic side of things, and the guy who had been doing that left,” White said. “So I took that position at that point. Academics became my area for the rest of my time there.”

Moving from on-the-field responsibilities to the academic side at South Carolina was not a difficult transition for White.

“I was not a super coach,” White laughed. “I played high school football. I wanted to be like my (C.A. Johnson) high school coach, Charles Bolden. I wanted to help some young boys like he helped me to understand that I could be somebody in spite of anything. That’s why I got into coaching. My role there was to help any young kid who came through there. I wanted to make sure that those first black athletes had a comfort zone here so they could do what they needed to do to graduate.

“Over all of the years that I was there, I didn’t care if you were black, white, green or yellow. I wanted you to be successful. I started there because of black athletes, but once we moved on, the ‘black’ or the ‘white’ had nothing to do with it. The joy of my career with the University of South Carolina Athletics Department was that I had the opportunity to help so many youngsters ââ’¬” black, white, and whatever other color it may be.”

“Harold White helped everybody around him,” Manning said. “Not just young black kids. He helped everybody. He always stressed academics.”

White was inducted into the USC Athletics Hall of Fame in 2009, and is being inducted into the Richland County School District One Hall of Fame this month. While he is proud of the accolades, the 75 year-old takes more pride in staying in touch with the former student-athletes.

“I’ve received calls from all around the country from men and women thanking me,” White beamed. “That’s my life. That’s the kind of thing that keeps me going. I always enjoy meeting them and their children. That’s been my joy.

“Working with the athletes, both male and female, was the best part about my time at South Carolina. Through the years, I’d like to think I had some role in helping them become very productive citizens. I just like to hear that they are doing well.”

White and his wife, Lilly, have two daughters and four grandchildren. They are among the few who don’t call him “Coach,” but he is “just fine with that.”