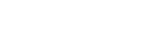

Team Effort is a Lifesaver for Will Riggs

Jan. 9, 2018

College swimming student-athletes don’t normally need a lifesaver. South Carolina sophomore Will Riggs had several, and he needed every single one.

One day at the end of spring semester last year, Riggs began feeling terrible stomach pain. It became strong enough that he was taken to the hospital. A short time later, he was on the operating table where things didn’t look promising at first, but the quick work of his doctors saved his life, and now he’s back in the pool, competing for the Gamecocks.

There were many people involved in between that played a part in Riggs being here to tell his story.

“I’m just so lucky that I have friends that are so willing to take care of me,” Riggs said. “It’s those really tight, great friends that I have that got me through and really saved my life, honestly. I’m just really thankful for that.”

“Everything fell in the right place,” said Dr. Hart Parker, a surgeon at Palmetto Health who performed the emergency surgery. “First and foremost, the people that were with him in his room and realized something was wrong and to make the call to bring him to the E.R. The quick response of the folks there to make the decision that indeed something was different with this gentleman, and to get him right in, image him, and make the call appropriately that something was wrong and needed intervention.

“I can’t quantify the time period, but any break in that perfect chain of events could have led to a very poor outcome.”

“The stars that aligned here during this whole thing were pretty amazing,” said Dr. Jeff Guy, Medical Director for South Carolina Athletics. “In dealing with our athletes, the response and the urgency involved is pretty amazing.”

A Typical Day

It was May 10, 2017, and Riggs was having a normal day. He had two practices and lifted weights. He later went out to dinner with friends, ate fried chicken, and took a nap.

One of my friends picked me up off the bathroom floor, and that’s when they realized something was really wrong.

Will Riggs

“Then I woke up, and I started having some stomach pain,” Riggs said. “It just felt like a normal stomach ache at first.”

Thinking the stomach ache would go away, Riggs planned to go and hang out at a friend’s house later that night. The stomach ache progressively got worse, and he later passed out from pain.

“One of my friends picked me up off the bathroom floor, and that’s when they realized something was really wrong,” Riggs said. “My pain was a `nine’ and on its way to being a ’10’ at that point.”

Riggs and his friends thought it might be a bad case of food poisoning.

“I didn’t want to go to the hospital at first because I just thought I was being a baby,” Riggs said. “Cody (Bekemeyer), my roommate at the time, called [Breanna Reyes], who is our athletic trainer. She said to go ahead and take me to the hospital. At that point, I could barely make it to the car, so clearly something was very wrong. All the way to the hospital I was just screaming. I was apologizing to my friends because I felt like I was acting like such a lunatic.”

South Carolina head swimming coach McGee Moody had received a text from Reyes that Riggs was headed to the emergency room. Riggs’ mother had been called and his father was soon in the car to drive down from Virginia.

From Bad to Worse

“On the way to the hospital, I remember saying `I don’t want to die,'” Riggs said. “I remember telling myself that I don’t know why I’m saying that.”

He arrived at Palmetto Health Baptist Hospital in Columbia.

“I remember spilling out of the car, on to the sidewalk at the emergency room,” Riggs said. “I couldn’t stand up on the sidewalk. They put me into a wheelchair. I just couldn’t find any relief from the pain.”

Riggs was given pain medication, but repeated doses and stronger pharmaceuticals didn’t ease his agony.

“I began to lose feeling in my hands and feet,” Riggs recalled. “I think I was coming in and out [of consciousness] at that point.”

Communication from Reyes and the doctors continued to keep the parents and coaches in the loop, and events escalated quickly.

“I received a call from her that they were at the E.R., that Will was in a lot of pain, and that they may have to do surgery,” Moody said. “A few minutes later she called and said they had decided to do surgery. Then in the background, I heard a bunch of commotion. There was concern.”

“Our system is built on communication” Dr. Guy said. “We called his dad immediately. I also let our Athletics Director know, Coach [Ray] Tanner, and I also spoke to the coach (Moody). Lastly, I spoke to Dr. Parker.

“He is one of our surgeons that are consultants for our athletes. I called him at home, and he had actually just got the call from the emergency room at the same time. He told me he was extremely worried about him. I put Dr. Parker in touch with his father.”

The vast majority of the times, this just does not turn out well.

Dr. Hart Parker

Emergency Surgery

After x-rays didn’t offer any solutions, a C-T scan showed the doctors what was wrong. Riggs couldn’t actually feel the effects of the pain medicine because his intestines were so twisted that they were cut off from the blood stream.

“He was in obvious extreme pain,” Dr. Parker said. “Based on all the information together, his vitals and how bad he looked, we realized there was little to do short of going to the operating room.

“Before that, I made a call to his dad. I explained what was going on with him and the gravity of the situation. Having children of my own, I can only imagine that kind of phone call. I told him the situation, the time frame, and that we had to move right now. I was honest with him and explained the real possibility of a poor outcome. I’ll never forget the words of him saying `so you’re telling me I may never get to see my son again.’ That really drove home to me the gravity and the people involved with him. There were so many of the university staff there with him.”

Riggs was taken to the operating room where they “opened him up” and it was obvious that there was no blood flow to his intestines. All of it was completely black due to a twist, or volvulus, in his bowels which had blocked off all blood flow.

“They were just as black as they could be,” Dr. Parker said. “It was just a heart-felt sag for me in the operating room, realizing that the likeliness of this turning out well was small. The advantage that he had was that he was young and healthy.

“I could hear his dad’s conversation with me in my mind. The vast majority of the times, this just does not turn out well.”

Dr. Parker was able to untwist Riggs’ bowels, and the prognosis quickly changed for the better as blood flow resumed, and the organs returned to a healthy pink color.

“It was just a wonderful feeling that potentially we had made a marked changed in his outcome,” Dr. Parker said. “When we opened up his abdomen and got that first appearance, the entire staff, we all realized this was not good. Then to see it `pink up’ was just the most amazing feeling.

“It seemed like an eternity in order to make things untwist, but in fact, in all you’re talking about just a few minutes. It’s a procedure you have to get in and get done pretty quickly.”

“I’ve been practicing medicine for 17 years, and this was probably one of the most amazing things that I’ve seen happen,” Dr. Guy added. “They basically took a part of his body that was not looking good and five minutes later, after correcting the problem, it turned into very viable, healthy appearing tissue. This is a situation where another half hour or hour or so, it would not have been possible.”

Parker noted that Dr. Juan Camps was the pediatric surgeon who helped make some key decisions throughout the process. The lines of communication, which Dr. Guy noted as being an important part of their process in taking care of South Carolina student-athletes, continued to flow throughout the ordeal.

“Everything took place so quickly,” Moody said. “I live about 25 minutes away from the hospital. I was about 15 minutes out, when I received the call and was told he might not make it through surgery. I was having this internal battle of what I was going to tell his parents. Before I could park the car at the hospital, Dr. Guy called me and said `this was the best save I’ve ever seen.’

“I had been calling Mrs. Riggs every five to ten minutes, and when Dr. Guy called me [the last time], I immediately picked up the phone and called her. Out of this being one of the most stressful nights of my coaching career; that was one of the best feelings of my coaching career.”

Despite all of the pain and a near death experience, Riggs said he felt a certain peace while it was happening.

“I think I knew that since I was in such good care that I was going to be alright,” Riggs said. “I guess I had so much trust in the doctors. I thought I was going to be OK, and that this wasn’t the end.

“The anesthesiologist really made me trust him. He told me, `we’re going fix you,’ and I trusted him.”

Remarkable Recovery

Despite the ordeal, Riggs never lost his sense of humor.

“Right before he went into surgery, he said `coach, I don’t think I’m going to make practice tomorrow, is that OK?'” Moody said. “I told him, `yeah, I think we’re good.’ Immediately, the next day, he’s asking the doctors when can get back in the pool and starting lifting again.”

We have to slow him down more than we have to speed him up now.

Coach McGee Moody

That didn’t stop the coaching staff from bringing some levity as well. During his recovery in the hospital, Riggs had to walk laps around the rectangle wing of the floor.

“Walking after surgery was really uncomfortable, and I remember one day, (Associate Head) Coach (Mark) Bernardino came in to the hospital,” Riggs said. “As I was walking my laps, he was walking with me. I kept seeing him look at his watch, and I said `are you timing me?’ Sure enough, he had his little stopwatch out and was seeing how fast I was doing my laps and encouraging me to get better. He always wants to improve me, which I really appreciate.

“I was so lucky to have all those coaches by my side while I was there [in the hospital]. Just being at the hospital until three or four in the morning just shows how much they care. You’re not just a number on a team. You’re so much more than that.”

Remarkably, Riggs was back in the pool on June 1.

“We have to slow him down more than we have to speed him up now,” Moody said. “He wants to press harder and harder. So we have to back him down a little bit.”

“Swimming was very uncomfortable,” Riggs said. “I worked really hard all summer in the weight room and in the pool to gain my strength back. I’ve come back to school and I feel like I can pretty much do everything I used to do.”

Less than a year later, life is good for Will Riggs.

“Now it’s just a story and a big scar,” Riggs deadpanned. “I had big things I wanted to do over the summer like going to World Championship trials, and the U.S. Open. I had to put all of that on hold.

“I’m here, and I say that every day. If there’s a little something going wrong, I don’t really dwell on it and kind of look for the bright side of things. You know, it could be much worse. I’ve got a lot to be really happy about.”

Looking back at the events of that night, Dr. Parker harkens back to the “many hands” theory a mentor had taught him years ago.

“Everyone touches the situation from the person who checks him in, to the person who gets them back, to the person who transports him to the C-T and the operating room,” Parker said. “All those aspects of care really make the whole package. The `many hands’ theory of care was certainly true in this situation, not only from our standpoint, but his friends and support staff that he had from the team. The coaches were there all the time. It was amazing to see the love of the Carolina community for him.”

Call them guardian angels. Call them lifesavers. Will Riggs had a lot of them that day.