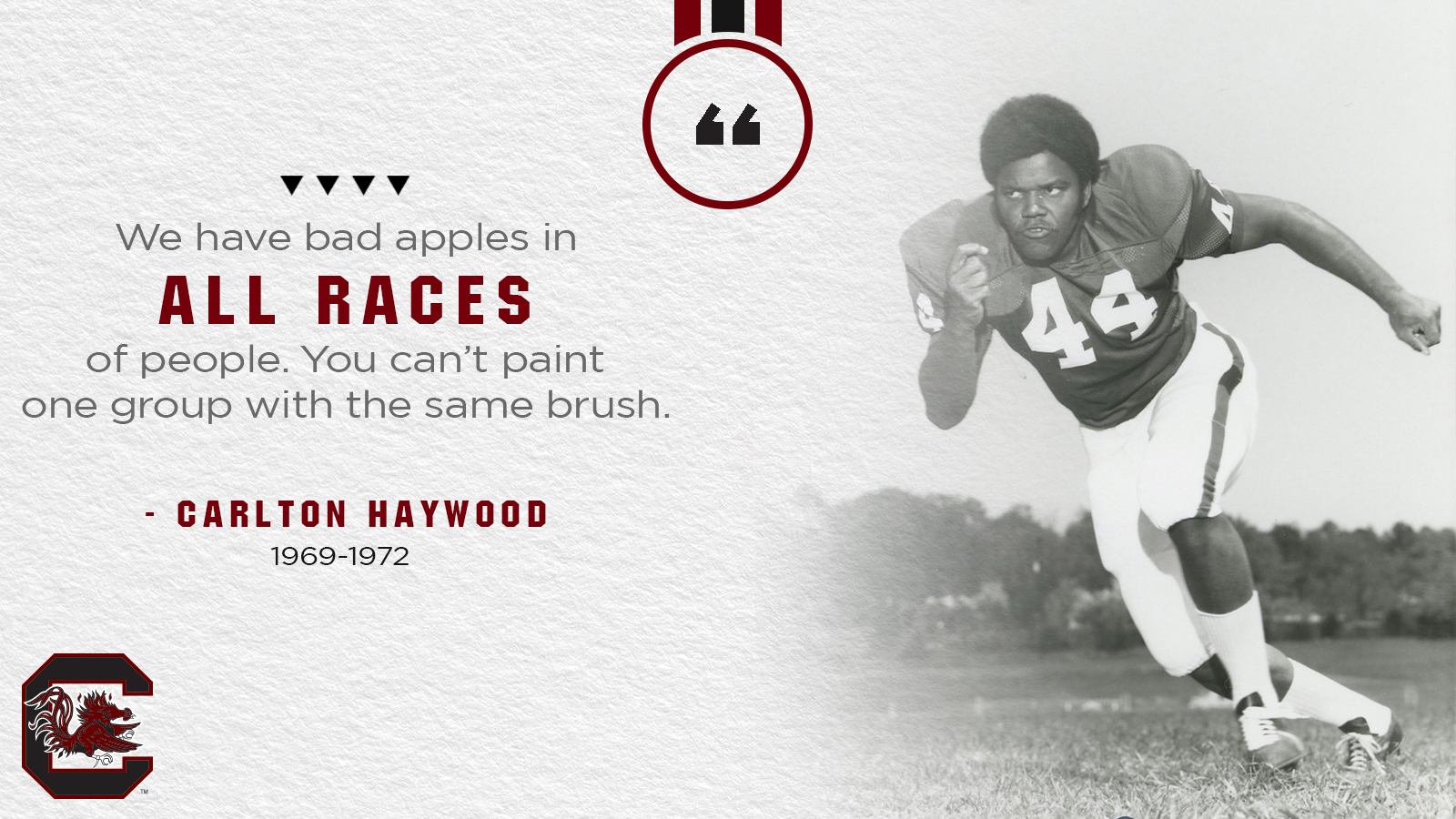

Football pioneer Carlton Haywood reflects on his place in Gamecock history

As the first black scholarship football student-athlete at South Carolina, Carlton Haywood earned his place in history as a pioneer for Gamecocks Athletics when he arrived on campus in 1969. The 68-year-old is humble about his role in South Carolina history, and while he certainly understands the significance, he wishes there didn’t have to be such milestones and is frustrated that racial problems still exist.

“Someone had to be the first,” Haywood said. “Sometimes someone in my family brings it up, and I get a little angry because why would I have to be the first? Why was it necessary to be the first?

“I recall the things I went through. I’ve seen things happen. The door opened with integration and all that kind of thing. It’s almost like the virulence of racist attitudes went underground and became a lot more subtle. I just wish people would understand that we’re people, too. We have the same aspirations in life as everyone else. We have bad apples in all races of people; black, white, Asian and whatever. You can’t paint one group with the same brush. All I ask is that people have open minds about humanity and not just based on skin color.”

The Macon, Ga., native is now retired and lives in Roanoke, Va., after a lengthy career as an area manager for the Ford Motor Company.

Haywood was recruited by South Carolina coach Paul Dietzel and his arrival on campus 51 years ago had mixed reactions initially.

“The first day I got to campus during the preseason, the football players come to the athletics dormitory, and my parents had to bring me up along with my high school girlfriend,” Haywood recalled. “Not everybody was as happy to see me as I was to be there. All of the sudden, you’ve got this African-American kid appearing in the lounge area, and normally they never saw African-Americans there except the kitchen help or a janitor. It was an eye-opening experience because the moment we walked into the lounge area of The Roost, people got up and scattered.

“Some of the coaches were there, and they walked up to my dad. He told me they said, ‘Mr. Haywood, don’t worry about it. We’re going to take care of your son.’ The reception wasn’t the greatest, but the rest is history.

“Some of my teammates that I saw that day, I never really got close to. Now, I’m only talking about a handful of people. Even today, I’ve had several opportunities to go back for homecomings and so forth, and to a man they always say, ‘hey man, forgive me for the way I used to act.’ I forgive them, but I don’t forget that kind of thing.”

While his initial reception wasn’t grand, Haywood said his recruiting experience with the Gamecocks was very positive.

“I was a young kid who hadn’t really been anywhere, and the guys at South Carolina showed a lot of interest in me,” Haywood said. “It was a very good opportunity. My visitation was an excellent experience. It was also the University itself. The fact that I had the chance to go to a major university was a good opportunity that I was glad I was able to take.

“Everyone was quite welcoming. It was a good experience, actually. I was there along with the first (black) scholarship basketball player, Casey Manning, and the first (black) scholarship baseball player, a guy named Jackie Brown. They made us feel quite at home. For a young guy coming from Macon, Georgia, I was very impressed and kind of blown away about how I was treated.”

With the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, there was a lot of turmoil around the United States, but Haywood was not concerned with being in the spotlight at a southern university.

“Not at all,” Haywood said. “I went to a formerly segregated high school. We integrated the high school when I was in the ninth grade. We had some experience and exposure to the kind of things that might befall us coming here. I wasn’t concerned because I knew I could handle whatever came my way.

“Steve Dietzel, Paul’s son, we still have a relationship where we can discuss things. He told me that his dad caught a lot of crap when signed me back in the day. Paul Dietzel was a good guy.”

“It was something that really built my character.”

That’s not to say there weren’t challenges beyond the usual difficulties for 17 and 18 year-olds moving away from home and making decisions on their own for the first time.

“One of the biggest challenges I can recall was my (first) white roommate because over the summer, leading up to that first year, his folks had to approve him rooming with an African-American,” Haywood said. “He caught more hell during that first year than I did because I guess a lot of the guys were afraid to come directly at me and say things. Behind the scenes, in subtle and not-so-subtle ways, he caught a lot of hell because he was rooming with an African-American guy. I don’t know all the situations he ran into, but I’m sure it was not very comfortable for him.

“I didn’t realize until later on the extent of the things he went through that were worse than I went through as far as discrimination.”

Haywood noted that there were occasions on the football field where he was singled out.

“I was a running back, and the tackles that happened to me in practice were a lot more vicious sometimes,” Haywood said. “Under the pile of humanity there would be an extra kick or punch or whatever. I had to be unafraid. It was something that really built my character.”

One of the biggest shocks in his first year at South Carolina came when one of his teammates, Steve Sisk, died from heatstroke after an intense training session in the summer heat.

“When the coaches announced that the next day, it was frightening,” Haywood said. “I called my mom and dad and said, ‘they’re killing us up here!’ That was the one time I almost thought about coming home.

“That was one of the worst experiences I could recall. There were a lot of small instances of overt and covert racism that I had to deal with, but nothing so onerous that turned me away. Generally speaking, everything was OK.”

Haywood said that as more black players were added to the team in subsequent years, the conditions improved.

“I was more or less the grandfather to the bunch, so I had to be a mentor to a lot of them,” Haywood said. “Today, a lot of those players who came in during my tenure, we’re best friends because of all the experiences we had in common. I like to say that some of them did not have to ‘pay the same tuition’ that I had to pay.

“The fans were generally open and commentary in local papers were fairly favorable, in general. The worst experience I had from a fan standpoint was not from South Carolina, but from some University of Georgia fans. That’s one of the reasons why, even today, one of the biggest rivalries for me is not Clemson, but the University of Georgia. When I was being recruited, Georgia didn’t have any black players. I had several players from my high school team that couldn’t carry water for me in terms of ability, and some of those guys got scholarships from the University of Georgia. When I came to Athens to play Georgia in the freshman football game, I was the only black player on the sidelines, I would hear the catcalls and the n-words. I had chicken bones thrown at me on the sideline. That was traumatic. My teammates didn’t know what to say.”

Haywood did feel added pressure to perform and he was dismayed by some nagging injuries as well. Despite having aspirations of becoming a dentist, Haywood felt some pressure to reluctantly change his major from biology to business administration/accounting where classes were more suitable to his practice schedule.

“I had to come to practice late a lot of times because of a chemistry class and all kinds of physics labs,” Haywood said. “It was always an issue. The worst thing about it was that I had several teammates who had the same kind of schedule, but the subtlety of the pressures I got, forced me to change my major because I didn’t want deal with the hassle the coaches were giving me or ribbing me because I was coming to practice late. I had no interest in accounting, but I had to get some degree that would be suitable for the future.”

Haywood graduated from South Carolina in 1973. After working for Ford Motor Company for 33 years, he retired in 2007. He and his wife, Walteena, have five children and six grandchildren.